Elm and the "tail end" - Part 2 - Displaying a "tail end"

Elm application life cyle

This is part 2 of a series, see the first part to get the jokes.

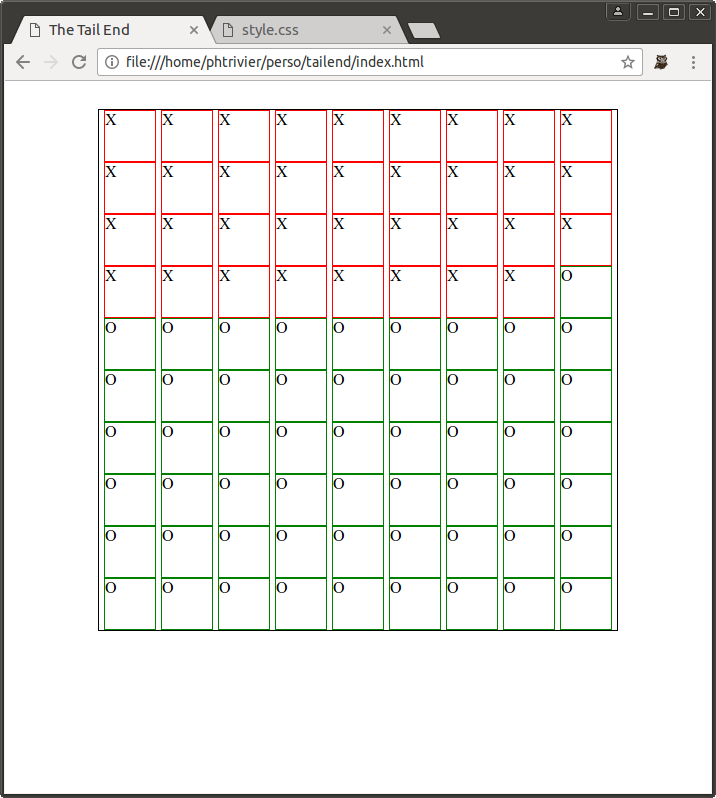

Let’s do a first simple version of our application, that simply displays a hardcoded failend image for a fixed setting.

The life of a Elm application is described better than I will do by its creator in The Elm Architecture.

The general idea is that, to make an application, you have to answer a few questions.

What is this application about ?

That’s your Model. The data of you application. It is just that. Data.

The scary and important thing is that all data of your application should live in one data type.

Imagine that in Javascript, instead of having your data scattered around your application (some associated to DOM nodes, some in a top level object, some in global variables, etc…), you have one root object, and everything should use that.

elm has a nice type system, so the “kind” of data you’ll manage is stricly defined.

(So stricly defined that it will make you cringe, some times - more on that later.)

In our case, what are we talking about ? We want do display a “tail end” graph, which means we have to give two information :

type alias Model =

{ age : Int -- How old are you ?

, expected : Int -- How old do you expect to live (no jinxing implied)

}

Note that I suppose you can call your Model type however you want. But let’s not surprise everyone ?

What can this application do ?

You capture all possible actions in a type Msg type. For our first version, things will be deceptively simple : the application can Start. And nothing else.

type Msg

= Start

A real life application would have to model everything that can

happen, and elm forces you to be a bit explicit about events that

would normally be “implicit”.

For example, there would be a Msg for user actions that make you

trigger an HTTP request ; and another Msg for when the HTTP response

comes back ; and another for when the HTTP response comes back with

an error.

The bad part is that you have to think about all cases early on. The good news is that you think about all cases early on !

How does this application start ?

This really ask two questions :

- what is the initial state of the application (that’s answered by giving a value of the

Msgtype) - should I do something right after starting ? (for example, go get a list of TODO items from an API, etc…)

In our case, the answers will be :

- I want to display the graph for a 35 yo person, who expects to live at least 1 to 90

- There is nothing to do once the application is started.

This is all captured in the init function :

initialModel : Model

initialModel =

{ age = 35

, expected = 90

}

init : ( Model, Cmd Msg )

init =

( initialModel

, Cmd.none

)

Where do we go from here ?

(Mandatory BTVS reference. Sorry)

Your application will then enter an infinite loop of going from a Model, to reacting to Msg, to a new version of the Model.

That’s your moment to play God / Mother nature / Game Master and set up the rules for your world.

As an apprentice “All powerfull being”, your first set of rules would be simple :

“Let everything stay the same and never change. Time for a beer.” (Lazy Creator, on a Friday.)

update : Msg -> Model -> ( Model, Cmd Msg )

update action model =

( model, Cmd.none )

Wait, aren’t we suppose to display stuff, too ?

Yes, because it’s a Web application. We’ll display the simplest thing that can possibly work : a div with div of fixed size. (Later we will use images.)

We’ll be using flex-box, because CSS is voodoo magic to me otherwise.

Implementing a view function

view : Model -> Html Msg

view model =

div [ class "page" ]

[ tailendView model ]

tailendView : Model -> Html Msg

tailendView model =

let

crossed =

model.age

uncrossed =

model.expected - model.age

in

div [ class "tailend-view" ]

((List.repeat crossed crossedItem) ++ (List.repeat uncrossed uncrossedItem))

crossedItem : Html Msg

crossedItem =

div [ class "tailend-box" ]

[ div [ class "tailend-cross" ]

[ text "X" ]

]

uncrossedItem : Html Msg

uncrossedItem =

div [ class "tailend-box" ]

[ div [ class "tailend-item" ]

[ text "O" ]

]

Some things to note:

- the goal of the ‘View’ function is to produce the whole page as a tree of ‘virtual’ DOM elements

- the function returns

Html Msg, because the DOM will be used to sendMsgto your application when your users interact with it. More on that later. divis a function from theHtmlpackage that produces virtual DOM elements. The package has plenty of other functions for most DOM elements. In general those functions take two arguments :- a list of attributes (here, the

classfunction from theHtml.Attributepackage is used to set the CSS class - a list of child

Htmlnodes (returned by other functions fromHtml. See thistext "X"stuff ? A virtual DOM nodes that says there should be some, ahem, text. “Turtles all the way down”, as they say.)

Also, note that the view is a pure function that only looks at the

model. I choose to create local variables that ‘translate’ the

Model attributes into a sort of “View model”.

Those computations would be run every time the view has to be re-displayed. This will probably make casey cry.2

The trick is to convice oneself that it probably does not really matter.

Don’t worry about precomputing values based on state — it’s easier to ensure that your UI is consistent if you do all computation within render(). Facebook team

Plus, if you have heavy things to compute, it is probably possible to cache results in a clever way.

Making things pretty

Some styling is of course necessary for that, which we’ll keep to a mininum.

Add a CSS file :

/* to create in src/css/style.css */

body {

padding: 20px;

}

.container {

padding: 20px;

}

.page {

margin: auto;

width: 80%;

}

.tailend-view {

border: 1px solid black;

display: flex;

flex-direaction: row;

flex-wrap: wrap;

}

.tailend-box {

position: relative;

}

.tailend-item {

border: 1px solid green;

margin-left: 5px;

width: 50px;

height: 50px;

}

.tailend-cross {

border: 1px solid red;

margin-left: 5px;

width: 50px;

height: 50px;

}

And edit your index.html

<!DOCTYPE HTML>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>The Tail End</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="./src/css/style.css" type="text/css"></link>

<script type="text/javascript" src="tailend.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<script type="text/javascript">Elm.Main.fullscreen()</script>

</body>

</html>

Voila, run make.sh again, and you should see something like this :

Which is not very good looking, but, as far as elm is concerned, everything is there.

We can either make this much prettier (which will only involve CSS), or add some interactivity to the page (in case you want to use other values than 35/90.)

That’s what we’ll do in next part !

-

Really, I mean it, *at least*. I don’t want to jinx it for anyone. Live long and prosper, etc… ↩

-

Seriously, though, give Handmade Hero a look, if you have like, another couple million hours of your life to spend, or something. Casey Muratori is giving a lot of great insights and advices and programming in a rigourous and non-bullshitty way. What he says mostly applies to native code (in particular games), so it’s a rather different world than web dev. And if you’re reading this, you probably want to do web dev. So this footnote is 50% name dropping, 50% irrelevant advice. And it’s becoming waaay too big. ↩